By Paul Wiley

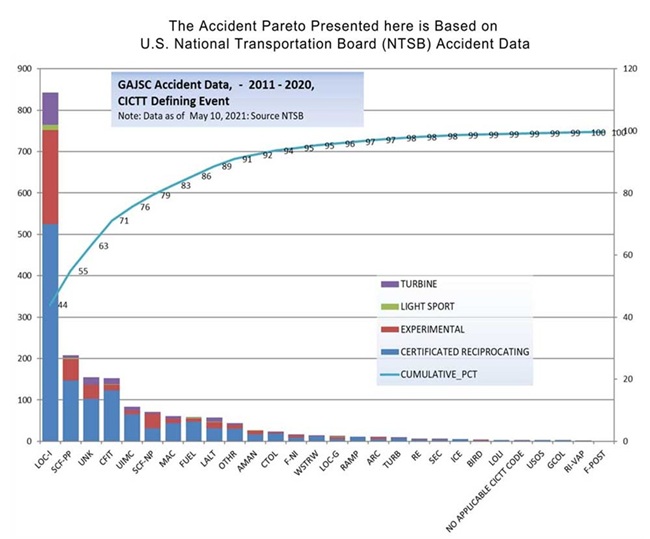

The FAA definition of Loss of Control - Inflight (LOC-I) is the “unintended departure from controlled flight”. LOC-I accidents are by far the most common category of accident as shown in the chart below from the US NTSB. LOC-I accidents account for almost half of all fatal General Aviation (GA) accidents. It has often been said that pilots must learn from the mistakes other pilots make because no pilot will live long enough to make all of the possible mistakes themselves. Accident prevention is why we study accidents.

This article will use a small sampling of LOC-I accident case studies to examine some of the causes of these accidents. Most LOC-I accidents are considered “pilot error”. It is generally believed that many of these LOC-I accidents could have been prevented had the pilot clearly understood the risk of LOC-I and taken timely action to prevent Loss of Control. Pilots should study these types of accidents to ensure they understand what causes LOC-I accidents and the associated risk. They should also practice with a flight instructor to develop the skill and then maintain that skill with regular practice to become proficient and to avoid LOC-I accidents.

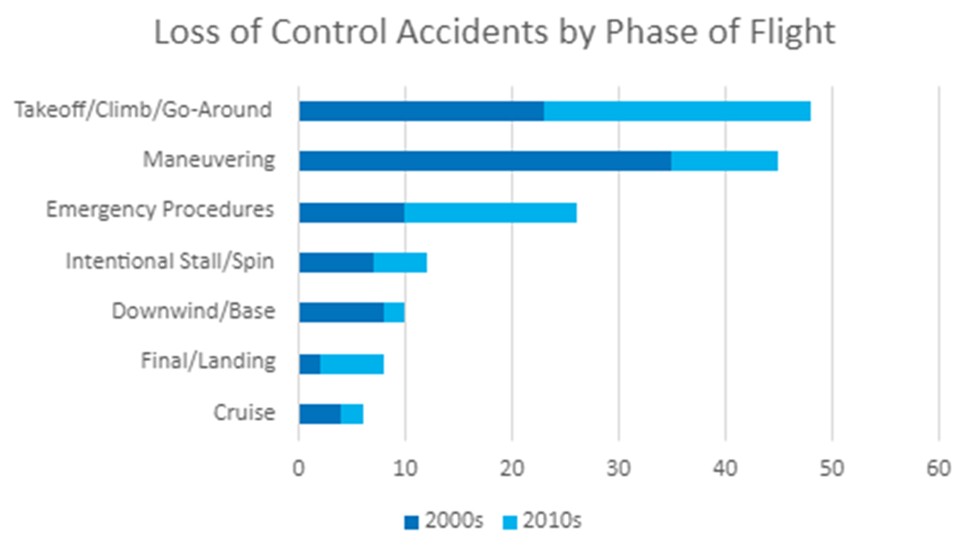

The chart below shows LOC-I accidents categorized by phase of flight. This data is further divided by data from the 2000s and data from the 2010s. It is clear that Takeoff/Climb/Go-Around is the most common phase of flight where fatal LOC-I accidents happen. It’s a good reason to think about every take-off, consider options in the event of an emergency shortly after take-off and practice the “impossible turn” with a CFI at altitude to be prepared.

While LOC-I accidents are most commonly caused by a stall or stall/spin, there are several other causes, including but not limited to: spatial disorientation (think continuing VFR into IMC), wake turbulence, and airframe structural limitations being exceeded by, for example, flying into a thunderstorm with associated extreme turbulence.

The following are case studies of accidents illustrating some of the common causes of LOC-I accidents. Included are links or references to additional information concerning these accidents. These case studies are taken from the AOPA’s Air Safety Institute database. Thank you AOPA!

Loss of Control: Phase of flight: Takeoff/Climb/Go-Around

Beechcraft G36

3 July 2021, Aspen, CO

On a hot summer afternoon, the Bonanza pilot requested a VFR departure and performed two climbing circles over the airport before continuing the climb in a valley to the northwest. Without sufficient climb performance to clear the rising terrain, the pilot continued a sluggish climb before starting a turn toward lower terrain, but it was too late. The pilot lost control and the aircraft impacted terrain, killing both on board.

All aircraft approach limits in high-density-altitude situations, and poor performance in such conditions, should come as no surprise. Always add a safety factor (AOPA recommends +50%) to performance calculations when planning such a departure.

For more information watch the excellent video from AOPA’s Air Safety Institute: Accident Case Study: Into Thin Air

Loss of Control: Phase of flight: Final/Landing

Cirrus SR22

16 December 2021, Knoxville, TN

The Knoxville tower instructed a Cirrus SR22 pilot to follow an Airbus A320 and cleared him to land. The pilot turned base about 1.8 miles behind the A320 and subsequently crashed. Before succumbing to his injuries, the pilot reported encountering wake turbulence on short final. He pulled the parachute, but the airplane hit the ground and burst into flames.

Wake turbulence is especially problematic because it's invisible. And it doesn't necessarily take an aircraft the size of an Airbus to cause problems for general aviation aircraft.

For more information see the Excellent FAA Advisory Circular: AC90-23 which goes into significant detail about wake turbulence and the effects on aircraft control.

Loss of Control: Phase of flight: Cruise

Piper 32-301

11 August 2022, Metz, WV

As the pilot of the Piper Saratoga tried to skirt a line of storms enroute to Myerstown, PA, he requested deviating 30 degrees left to “get over the top side of this stuff.” The controller warned of areas of extreme precipitation at 12 o’clock and five miles. After acknowledging that information, there were no further transmissions from the pilot.

As the airplane flew six more miles, it transitioned through areas of increasing precipitation until it entered an area of extreme precipitation. The radar track depicted a “steep, descending, right turn” until tracking was lost.

The aircraft fuselage was found inverted in hilly, wooded terrain an hour after the accident. The wings and tail section were separated from the fuselage and found over the following days. Pilots must understand the difference between strategic and tactical use of in cockpit weather information, including accuracy and time delays in reception.

While onboard weather can be an asset in avoiding problematic conditions, it should not be used to narrowly skirt cells. Onboard weather should be used for strategic avoidance of weather, never for tactical maneuvering around weather - especially thunderstorms.

For more information download the report: NTSB ERA22FA368

Loss of Control: Phase of flight: Takeoff/Climb/Go-Around

Beechcraft V35

16 July 2021, Angwin, CA

After overshooting the final approach course to runway 16, the pilot made a correction, landed on the runway in a series of bounces and initiated a go-around near the departure end of the runway. A witness reported that “after clearing the first set of trees, the airplane pitched up, the left wing dipped down and the nose dropped toward the ground and out of sight.” All three on board died in the accident. This type of accident is unfortunately all too common and all too often fatal.

Approaching to land with too much energy can result in a pilot-induced oscillation and bouncing on the runway. The best antidote is to perform a go-around, but it must be initiated early enough in the approach to clear any obstacles ahead and executed properly.

For more information download the report: NTSB WPR21FA273

Loss of Control:

Cessna 140

20 May 2022, Wayne, NE

A Cessna 140 pilot participated in a STOL event and turned final behind another aircraft in the competition. Forty-five seconds before the accident, a member of the ground crew radioed to the pilot and said, “Lower your nose. You look slow.” Shortly afterward, he repeated, “Lower your nose.” Instead, the 140 rolled to the right, entered a spin and impacted the ground. It appeared the pilot was attempting “S-turns” on final to maintain adequate distance from the airplane he was following.

This is a classic example of a stall/spin while maneuvering on final approach.

For more information watch early analysis by AOPA Air Safety Institute’s Richard McSpadden at this link: Early Analysis: N76075 - Cessna 140 Crash

Loss of Control: Phase of flight: Takeoff/Climb/Go-Around

Cirrus SR20

9 June 2016, Houston, TX

A Cirrus SR20 pilot made multiple attempts to land at Houston Hobby Airport. On each go-around, the pilot pitched up and raised the flaps at a lower airspeed. On the third go-around, she retracted the flaps well below the recommended POH speed. The aircraft entered a spin and descended into a parking lot, killing all three onboard.

While stalling on the final segment of the approach is always something to avoid, at least as many LOC accidents occur during a botched go-around maneuver.

For more information watch AOPA’s Accident Case Study: Traffic Pattern Tragedy

The common thread in all of the accidents described in this article is the loss of control by the pilot. Pilots can avoid LOC-I accidents by thoroughly understanding the cause(s) of LOC-I (primarily stalls), understanding the risk inherent in stalling the airplane, especially in the high-workload and potentially distracting traffic pattern environment at low AGL altitudes. It is recommended that pilots practice LOC-I scenarios with an instructor at altitude until achieving the skill and proficiency necessary to avoid LOC-I.